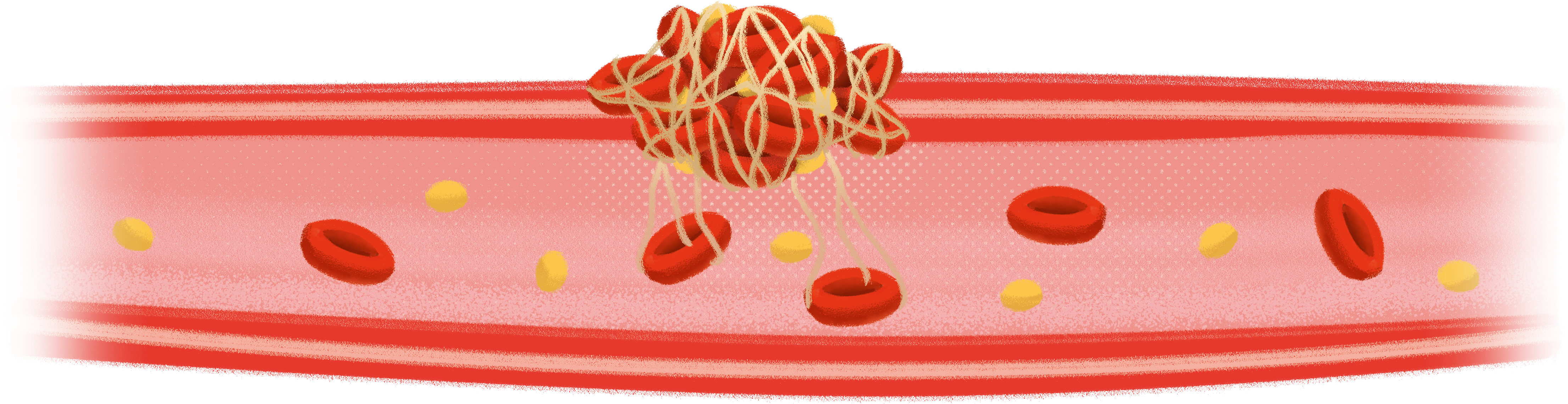

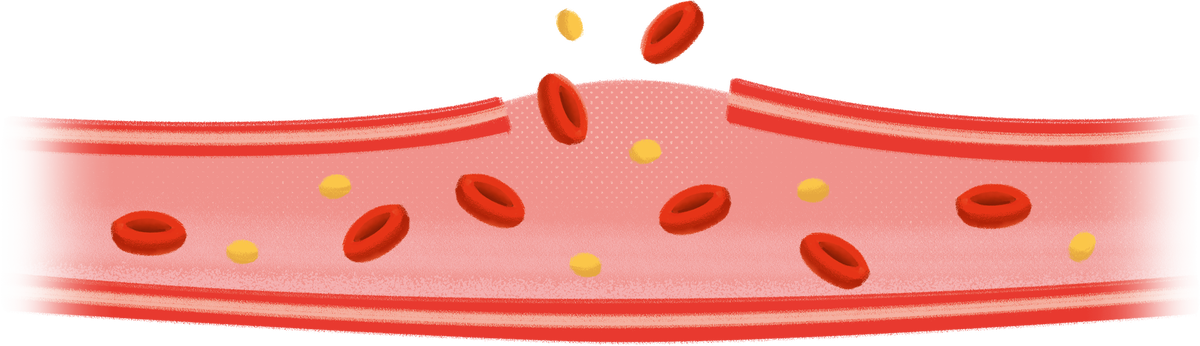

Rodenticides may remove pests, but they also plague raptors, preventing their blood from clotting appropriately. According to Juli Ponder, DVM, MPH, executive director at The Raptor Center (TRC), there is currently no readily available mechanism for testing the ability of birds to clot blood, which is important because clotting blood prevents excessive bleeding after trauma. “We needed something to use in the field or in the clinic to measure blood coagulation in our patients during the diagnostic process,” she says.

TRC hasn’t landed on a solution just yet, but TRC recently collaborated with across-the-street neighbors, the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine’s Veterinary Medical Center (VMC), to see if the technology used for domesticated pets and large animals would effectively test raptor blood. Ponder worked with the VMC’s clinical pathology lab, currently led by Daniel Heinrich, DVM, DACVP, assistant professor in Veterinary Clinical Sciences, to utilize the lab’s turbidimetric analyzer, which offered new insights.

“We use the turbidimetric analyzer to assess the body's ability to clot blood and identify some risk factors for bleeding,” says Heinrich. “All of these parameters are routinely tested in companion animals, and sometimes large animal species, here at the VMC. The analyzer has the capacity to program many other tests for clinical or research purposes, which provides much potential for scientific advancement.”

Traditional machines reveal when blood is clotted, but the turbidimetric analyzer also graphically reflects the formation of a blood clot over time. This helps clinicians gain a deeper look at the potential stability of a patient’s blood clot, rather than just confirming whether or not blood is clotted. Ponder says that, when their study wraps up, this will be the first example of a turbidimetric coagulation machine being used to validate blood samples from birds.

TRC and the VMC tested the blood of bald eagles, red-tailed hawks, and owls. The findings were surprising: each species showed up differently on the test.

“Normally, we can only diagnose rodenticide toxicity post-mortem. It would be ideal to be able to identify when raptors have been exposed before they severely coagulate blood or die,” Ponder says. “This technology allows us to plot a raptor’s exposure and better anticipate their care needs.”