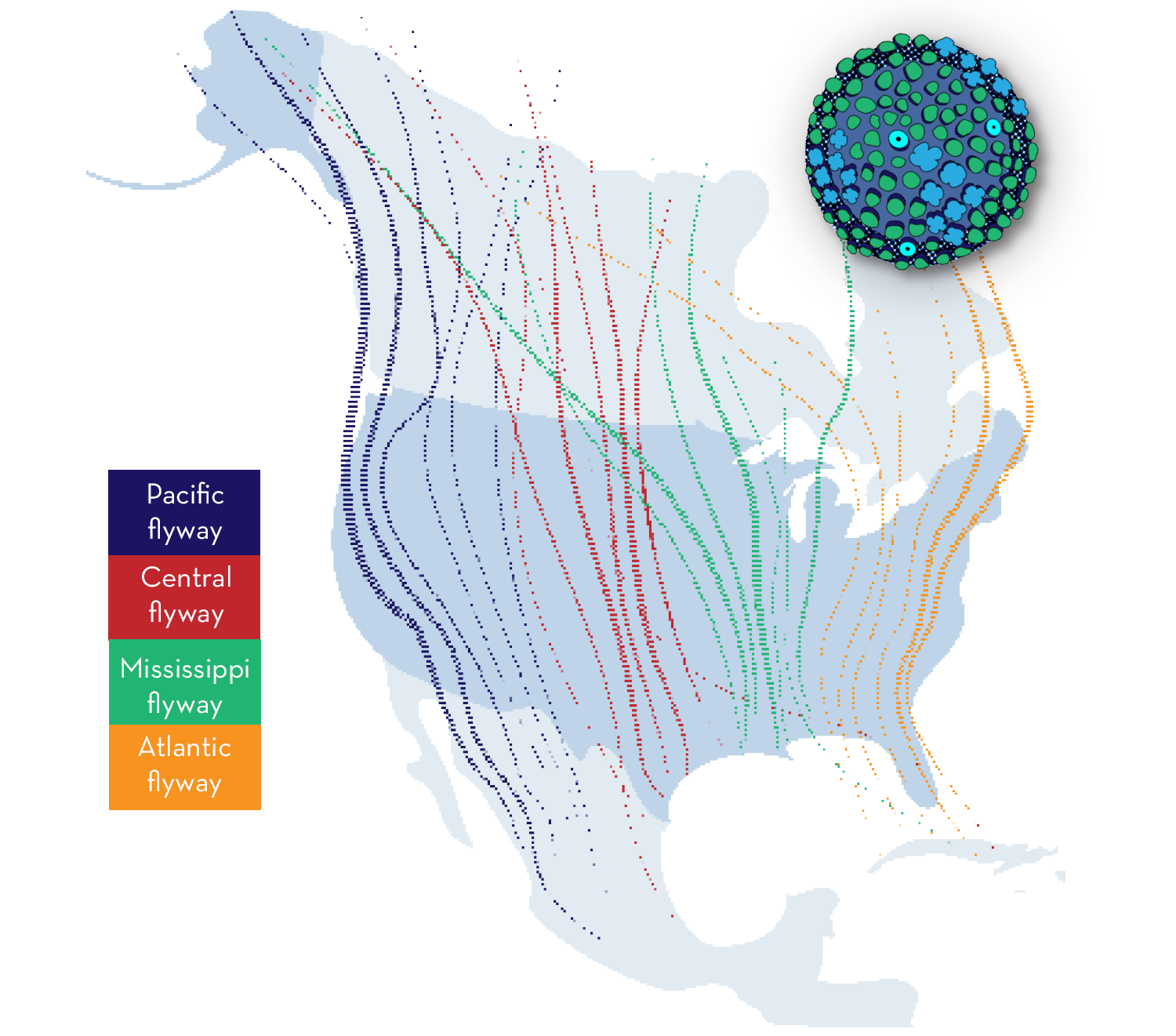

When the first migratory birds hit the skies in spring 2022, trouble came with them. Over the past year in Europe, a deadly disease called highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) was circulating and hitched a ride on birds making their spring migration in North America.

Unlike previous outbreaks of this virus, this year’s HPAI strain spread more rapidly and fiercely in wild birds along migratory routes in the U.S. and Canada. It infected wild populations and poultry operations alike. With an estimated mortality rate of 90-100 percent in raptors, the virus left devastation in its wake.

Staff at The Raptor Center (TRC) knew it was a matter of when, not if the virus would reach bird populations in Minnesota. A nearly five- decade history of excellence in raptor and ecosystem health combined with a record of preparedness for disease response allowed staff to spring into action on the frontlines of the outbreak.

While many other wildlife rehabilitation centers closed their doors or stopped admitting certain avian patients, TRC staff rallied to continue providing care to injured raptors and collect data on each case to better inform their biosecurity protocols and responses to future outbreaks.

“Because we decided to safely stay open and keep receiving and treating birds, we were able to collect probably the largest source of raptor data at one time, in one location that’s ever been collected during an active outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza,” says Dr. Victoria Hall, executive director of TRC. “And because of that, we then became a substantial source of data to the global community about HPAI, especially in wildlife rehabilitation.”

CAREFUL CARE

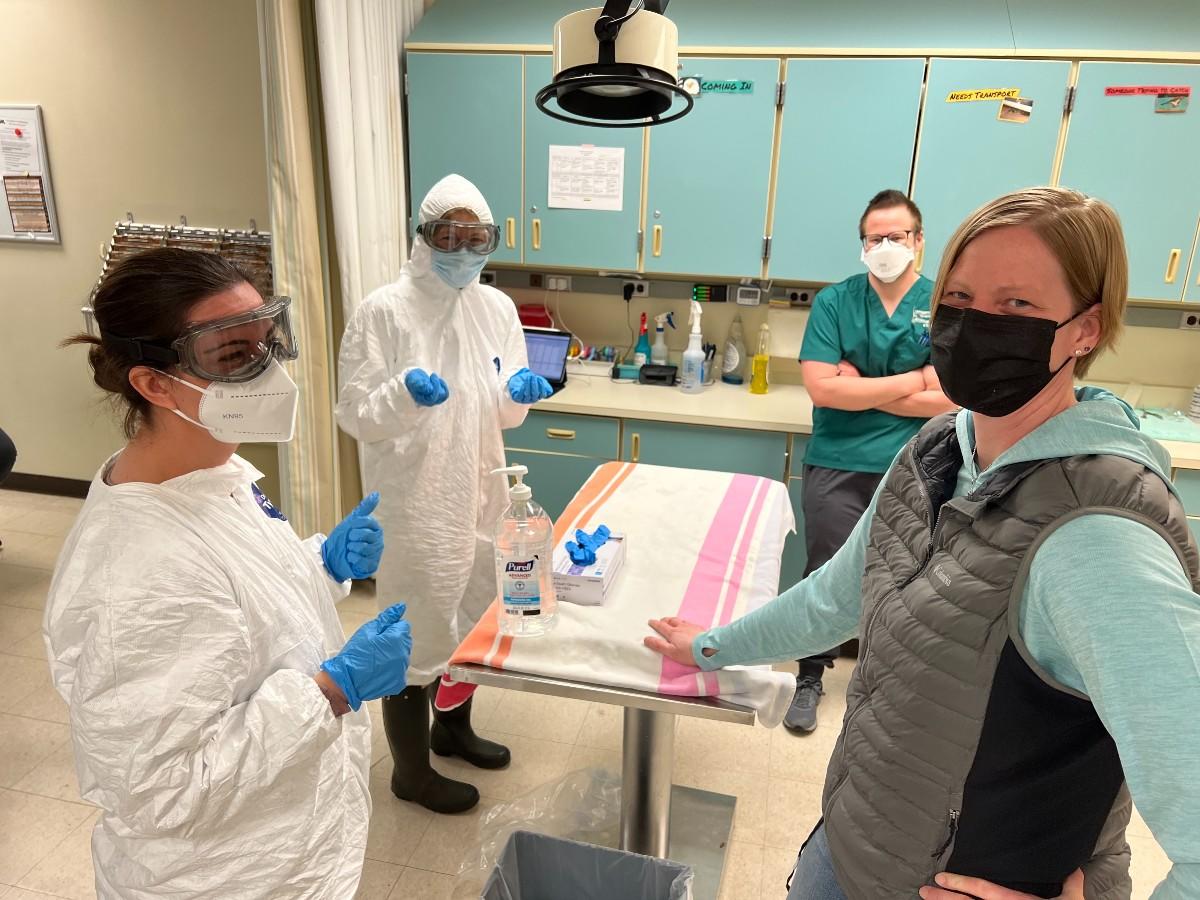

Staying open in the midst of a pandemic meant the daily operations of TRC would need to drastically shift in order to safely admit new patients and preserve the health of current patients, education ambassador raptors, and staff members.

That meant using existing research to inform, develop, and adapt biosecurity protocols. Quarantine procedures were created and revised. Visitors to the center were prohibited as the virus can survive on surfaces such as shoes and spread to new areas and hosts.

To safely admit new patients, TRC staff retrofitted a nearby building to serve as a space to conduct intake exams, administer basic medical treatments, and isolate raptors for their first round of quarantine. Patients then underwent a second round of quarantine in TRC’s lower level.

“Quarantine groups, personal protective equipment, testing, and more disinfectant than you could ever imagine allowed us to admit hundreds of birds over the first four months of the outbreak without any virus transmission escaping our quarantine process,” Hall says.

Containing HPAI is critical as the virus can spread through anything exiting a raptor’s body, including feces and respiratory secretions. It has a range of clinical presentations, but symptoms that stem from its impact on the bird’s brain and central nervous system are often the most apparent.

“The type of clinical signs we see depends on which part of the brain is affected. Abnormalities range from being very quiet and seemingly unaware of their environment to uncoordinated movements and seizures,” says Dr. Dana Franzen-Klein, medical director of TRC.

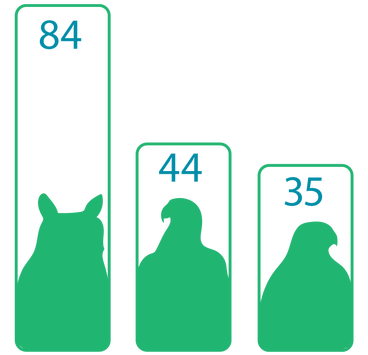

Recovery from HPAI is extremely rare thus far in raptors, and a vast majority of raptors infected with the virus die or are euthanized. From March 28 to Sept 4, 2022, TRC tested 701 individuals for HPAI upon admission to TRC, with 187 raptors testing positive for the virus. One great horned owl beat the odds, recovered from HPAI, and was released in May.

The extensive testing and extra biosecurity procedures significantly increased TRC staff workload, but the dedication of its members helped the center carry on its mission through the worst of the spring outbreak.

“The staff put in a lot of hours and a lot of effort,” Franzen-Klein says. “It took blood, sweat, tears, and passion to be able to do what we did. Our staff definitely went above and beyond to make it happen.” The community also played a significant role in helping TRC navigate the outbreak. Members of the public called in sightings of birds in distress and gave financial support to cover increased costs associated with the heightened biosecurity measures, such as purchasing personal protective equipment and other medical supplies. Volunteers also provided vital transport services for birds found around and outside of the Twin Cities.

GLOBAL REACH

Throughout the pandemic, TRC’s impact extended beyond the patients in its clinic. Each raptor admitted represented a trove of data that could be used to help organizations across the world.

Collaboration among these organizations, which included other wildlife rehabilitation centers, zoos, government health agencies, and agricultural operations, is vital in tracking and responding to HPAI outbreaks.

In this ongoing 2022 outbreak, virus transmission has ramped up during fall and spring migrations. As wild birds move, so too does the virus, increasing the chance that it can jump from wild birds into poultry. The USDA estimates more than 40 million birds in poultry flocks across 36 states were infected during the 2022 spring outbreak.

The total impact on wild bird populations remains unknown as testing continues, but more than 2,200 confirmed HPAI cases in 44 states were reported to the USDA by state and federal wildlife agencies as of July 2022. Cases detected in wildlife rehabilitation are not included in any federal data.

As part of its HPAI outreach efforts, TRC staff created resources, shared patient data, hosted webinars with international attendees, and much more to help educate others across the world.

And the center isn’t done. As the fall migration began, Minnesota saw the return of HPAI in both poultry operations and in wild birds. Decisions regarding a response to the virus require data and to help gather more of it, TRC is conducting a serological survey on new admissions. This type of survey is a blood test used to detect antibodies and will help shed light on if there are raptors in the wild that are surviving the virus at higher rates than previously thought.

“We're going to be drawing blood on every bird that comes in this fall and spring to try to look for evidence of birds who have recovered to better understand what the virus is really doing to these birds,” Hall says.

TRC also will continue to collaborate with partners across the world to increase disease response capacity— for HPAI and beyond—at zoos, wildlife rehabilitation centers, and poultry operations.

“This disease, in particular, circulates on a global level,” Hall says. “It’s not a United States problem. It's not a North American problem. It's a global problem. It's not just an agriculture or wildlife or human problem—it impacts everything. You have to have a collaborative ecosystem health approach if you want to address it.”